Guitar World | September 1992

- Faith No More Followers

- Mar 27, 2024

- 10 min read

PAUL AND STEVE BLUSH

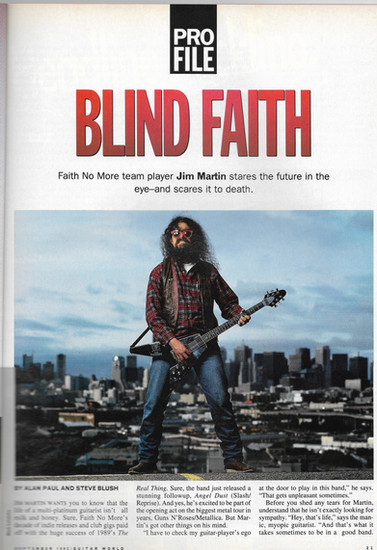

Faith No More team player Jim Martin stares the future in the eye-and scares it to death.

Big Jim Martin wants you to know that the life of a multi platinum guitarist isn't all milk and honey. Sure, Faith No More's decade of indie releases and club gigs paid off with the huge success of 1989's The Real Thing. Sure, the band just released a stunning follow up. Angel Dust (Slash/ Reprise). And yes, he's excited to be part of the opening act on the biggest metal tour in years, Guns N' Roses/Metallica. But Martin's got other things on his mind.

"I have to check my guitar-player's ego at the door to play in this band," he says. "That gets unpleasant sometimes."

Before you shed any tears for Martin, understand that he isn't exactly looking for sympathy.

"Hey, that's life," says the manic, myopic guitarist. "And that's what it takes sometimes to be in a good band. Remember that, kids."

And remember this: just because Martin's role in Faith No More is different from that of your average power-chord master, it doesn't mean he's not important to the band's sound. Though he rarely solos at length, his Hetfield/Iommi-styled riffs are a critical part of the band's musical mix, toughening up Roddy Bottum's prominent, textured keyboards and preventing Faith No More from spinning into over-intellectual, prog-rock land.

Like The Real Thing, Angel Dust is a dense, extremely challenging album, full of wild time changes, discordant notes, Mike Patton's animalistic grunts and caustic white-boy raps—and Martin's strange, eerie guitar fills. On "Malpractice," which veers toward death metal, Martin rips off an extremely discordant 12-bar solo. His sweet, melodic solo flutters through layers of samples on "Smaller And Smaller," and he drives "RV" with crisp, twangy blues fills. Then there's "JizzLobber," Martin's gnarly personal composition and one of the album's finest moments.

Martin's personal behavior is no closer to what one would expect from a guitar hero than his playing. Which other rock star would be found bowling in his regular Sunday league the morning after appearing at Oakland Coliseum's prestigious Day On The Green-festival with Metallica, Queensryche and Soundgarden? Lucid, approachable and refreshingly real. he is the Faith No More member least affected by the band's sudden success. He still lives at home with mom and still hangs out at the cheap East Bay dives he's always frequented.

We spoke to Martin as he prepared his mint 1988 Harley Police Special for a grueling 12-hour cycle ride to the Grand Canyon. It was a final chance to unwind and have some time to himself, he explained, "before the band hit the road and all the craziness starts again.

Guitar World: Angel Dust is a very ambitious album, in terms of time changes and mood swings. Did you set out to create such a richly textured album?

JIM MARTIN: I could say yes, because I know exactly what you mean. But Id have to say no, because when we were recording, I was only thinking about the particular song we were working on. Some of the other guys may have been thinking conceptually or trying to set a consistent mood, but I was just trying to play the right part for the right song.

GW: Your guitar's primary role is to toughen up the keyboard lines. Were your parts on Angel Dust actually written to double or complement the keyboard lines?

MARTIN: Sometimes, but when I'm involved in the writing of a song, I write for the guitar. I wish we always did it that way, but on this album a lot of keyboard parts were written first, so I "was actually trying to write my guitar lines to match—to "toughen" them, as you said. It's definitely challenging—and, after much noodling around, I usually end up using the simplest possible thing.

GW: But some of your fills, though brief, are pretty bizarre.

MARTIN: That's right. The fills are where I do my warped little thing; I throw in whatever I can get away with without the other guys shooting me. It can be frustrating, but I really can't complain.

GW: Your fills on "RV" have a great, twangy sound. Did you use the bar there?

MARTIN: No. Actually, it's done with an Eventide H3 000 S Utra-Harmonizer. I also used a Strat there, because I wanted it to be real clean and twangy. In some other spots on the album I used a Fender Tele Deluxe and a Les Paul Deluxe. The rest of it was recorded with my old favorite—my customized '79 Gibson Flying V.

GW: Was it custom-made for you?

MARTIN: Hell no I bought it new in 1979 and have slowly changed it over the years. It's got a Kahler tremolo bar, a Seymour Duncan Live Wire in the bridge position— which is a great, crunchy pickup—an EMG 60 in the nut position, a chrome-plated brass pickguard and some other various modifications. It resonates well, sounds great acoustically, and feels like home. I've got another V, and it's okay, but not nearly the same.

GW: Considering how attached you are to that guitar, do you ever get paranoid about having it on the road all the time?

MARTIN: Nah. I just figure that if anything happens to it, I'll get used to a new guitar, and eventually it will feel like home, too. Sort of like moving, [laughs]

GW: Your solo on "Smaller And Smaller" is very melodic, and has a distinctly Eastern flavor. Did you use an altered tuning on that?

MARTIN: No, it was standard tuning. I didn't really know what I was doing. The whole song sounded Middle Eastern to me, so I just noodled up and down the fretboard until I found the sound which I heard in my head. That's what I always do. I'm not a very schooled player.

GW: "Malpractice" is a very heavy song. In fact, it's almost like death metal.

MARTIN: Yeah, that's pretty out there. I feel like I'm basically an actor in a play on that song, because Mike wrote it and I essentially had no input; I'm just playing his part. I usually write my own guitar parts, and I don't think I would have come up with anything quite like that. Death metal's not really my cup of tea. But then I don't know what I could call my "cup of tea." I hear new music that I like, but nothing's really inspired me like the first guys—Zep, Skynyrd, Floyd and Sabbath.

GW: Speaking of inspired, "Jizz Lobber" is a real showcase for you. Did you see it as an opportunity to stretch out?

MARTIN: Not really. I just wanted to have a song of mine on the album, and I wanted to write something really horrible and ugly. The title is my idea of a joke, because I'm not really a fan of true guitar-jizz music. Of course, I can't play like Satriani or Vai any how. I feel like those guys are playing another instrument altogether.

GW: What kind of rig did you use on the album?

MARTIN: It was basically the same as my live setup. I run my V through a Morley Power Wah fuzz—the old-style 110-volt one—an Eventide H3000S Ultra-Harmonizer and a little delay into a Mesa/Boogie Mark IV to four Marshall cabinets. It's good enough for now, but I'm always changing it in some little way. I think that the whole thing is over if you're ever completely satisfied with your guitar sound. My only major change since the last tour is that I-used Marshalls instead of the Mesa, but I blew an amp and it just hasn't been the same since the repair.

GW: What was your first experience with a guitar?

MARTIN: Well, my mom actually has a picture of me playing guitar when I was just a wee child, maybe five years old. I'm standing there in my cowboy hat, playing this toy guitar my old man got me.

GW: What type of music did you play at five?

MARTIN: Nothing; I couldn't play. I didn't actually start playing seriously until seventh grade, when I started jamming on my cousin's old Rickenbacker through a little Fender Champ amp. Before that, I played on my Mom's Harmony Patrician, a great old guitar. Eventually, my folks got me a Japanese Epiphone and a piece-of-shit Yamaha amp for Christmas, and I started playing Black Sabbath tunes. The first song I learned was "Iron Man," then "War Pigs"—which we still cover.

GW: You played with [original Metallica bassist] Cliff Burton in a couple of bands. How did you hook up with him?

MARTIN: I was playing Zep and Skynyrd covers in a neighborhood band called Easy Street, which was named after a strip club that we started going to when we were 15.

Our bass player quit, and he told us about Cliff. We started playing with him and he was already really good, way better than any of the rest of us. And he also looked pretty much the same as he did when he was in Metallica: bellbottoms and huge hair. He knew Puffy [FNM drummer Mike Bordin] and got him to join the band. By that time we were writing original stuff, which I still have some tapes of. We had a song called "Retarded Guys" that sounds similar to Nirvana's "Come As You Are." That band was together for over five years, but Puffy didn't last too long, because he talked too much shit. He joined some pop-punk band.

GW: You're probably the least punk-influenced member of Faith No More.

MARTIN: Yeah, I didn't get into punk until Cliff turned me on in the early Eighties. I was still listening to Sabbath, Zeppelin and Floyd, and Cliff introduced me to bands like Fear, GBH, Black Flag and the Exploited. That stuff was pretty wild; it was exciting and new for me. Cliff turned me on to a lot of cool stuff when he was in Trauma, though I can't say I was a big fan of theirs.

GW: What were they like?

MARTIN: They were kind of like—what's that band with the drummer with one arm?

GW: Def Leppard.

MARTIN: Yeah, those guys. I didn't really pay much attention to them, but they played around a lot and I used to go see them just because of Cliff.

GW: What were your impressions of pre Cliff Metallica?

MARTIN: I told him not to join. I said, "Fuck those guys, they suck." I just thought they were stupid. When Hetfield called up Cliff and said that they wanted him to join, I went with him to see Metallica play with Bitch at the Stone in San Francisco. Cliff was saying, "Geez, this is kind of weird. These guys want to talk to me about joining their band, and their bass player's still here." Then we were standing outside and Metallica's roadies got busted for stealing beer from the club. Cliff was like, "I don't know about these guys." It was pretty funny—especially in retrospect.

GW: How did that period lead to your joining Faith No More?

MARTIN: Well, around 1982-1983, I was playing in a whole bunch of bands. A lot of guys get the ridiculous, pointless idea that they can only play in one band. I would play with anybody, as long as I was playing gigs. All I wanted to do at that point was to go out and torture people. I was gigging a few nights a week, and practicing every day. One day I visited Cliff, and Puffy and Bill [Gould, FNM bassist] were there. They said we should get together to jam. I said, "Screw the jam. Why don't we play a gig?" So, Bill said, "We have a gig in two days. Come play with us." We went out and played as the Chicken Fuckers, and Bill drew a picture on the front of Puffy's bass drum of a chicken with a human dick shoved in its mouth. That was the start of the whole ugly thing. I started playing with Roddy and Chuck [Mosley, original FNM vocalist], along with those other two guys, and it all went downhill from there.

GW: Soon after that came the indie Faith No More album, We Care A Lot, which wasn't exactly a big-budget recording.

MARTIN: Yeah, that's yet another reason that record sounded like shit. We'd just started playing together, and that record sounded like it. Then we toured America in a four-door pickup truck. We definitely got a pretty sketchy response.

GW: The tour for The Real Thing lasted over a year and a half. How did you survive?

MARTIN: We almost didn't, my man. I mean, by the end of the tour I seriously wondered if I could ever play the guitar again. It just wasn't fun anymore. I was so tired of my rig that I just hated the sound and found it incredibly grating. But I don't think the problem was really my rig, which, as I said, is almost the same now and sounds fine. We only had one album of material with Mike, so we were playing the same dozen songs for a year and a half, and it got stale. I think we were all losing it by the end. That kind of tour is not the type of thing you try to repeat. It was probably necessary for us to be out there, because it took the album a long, long time to build and become successful, but being on the road that long becomes dangerous to your mental stability. When we finally got home, I took a good long rest, because I felt like I had nothing left to give. I'm never going to mess myself up like that again.

GW: Has playing become fun again?

MARTIN: Yeah, but it's a slow and ugly process. We had to deal with a lot of bullshit making this album, which definitely didn't help me get psyched to play again. Some people thought we weren't together enough to go into the studio, but we told them to get lost and went about our business. But I' m not gonna let all that prevent me from digging on the most important thing in my life—playing my guitar. I've been writing a lot recently, and I think just sitting at home and doing that really helped my frame of mind. So I am finally enjoying playing again, and I think I'm coming up with some of my best stuff ever.

GW: Are you content with the current sound and direction of the band?

MARTIN: I don't really like how we sound, to tell you the truth. We've got this big dumb sound, and everything else is lacking. As far as I can tell, they want me to play along with the bass, but I fit in my own stuff. When I first started working with them, I figured that they needed my help, they needed that huge heavy guitar, because they were some pretty weird guys. But things are getting better; we've come a long, long way since our very first album. Basically, I just try to fit in some guitar ugliness.

GW: From a guitar standpoint, how has Mike Patton's input influenced the band?

MARTIN: Well, he helped improve everything about the band a lot, which gives me more confidence and freedom to do my thing. His input has really helped open things up; there isn't as much tight control over who's writing the songs. There's still those people who make most of the songwriting decisions, but on this album there's a song by Mike and a song by me. And they're both really ugly. But it didn't come easy. Mike had a hard time fitting in at first, and he" s definitely got a bad temper. But everything settled down, and we're very happy that he's become an ugly man; at a certain point he became a filthy pig instead of a pretty boy.

Comments